I am ashamed to admit that I wavered on whether or not to write about this subject, despite writing about so many other difficult and sometimes personal topics.

Miscarriage impacts about 1 in 4 pregnant women, and it has impacted me multiple times. It is a difficult subject for any person, particularly those who have experienced it. When I was writing The Fictional Woman I had thought about writing something of my miscarriage in 2009 and later changed my mind. It was too dark and unwelcome a memory, and now I had a little girl, had started my own family, and I was not keen to revisit that experience.

And then it happened again. I could not shy away from it. I could not ‘forget’.

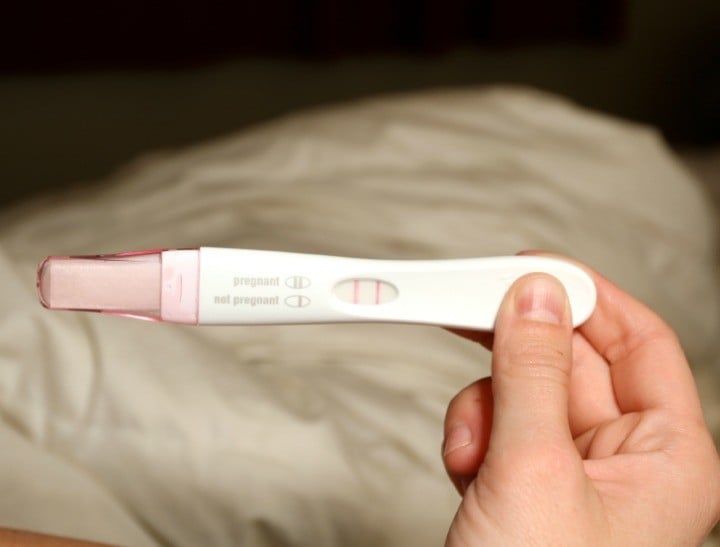

For only two sweet days my family and I had been delighted by the news of a positive pregnancy test. I’d felt the changes in my body one night and I knew. I could feel in my body that something was different, just as I had with both of my previous pregnancies. And then there it was in the morning, that crucial second line on the store-bought pregnancy test. We were in Hawaii (above), with family gathered from three continents to holiday together and celebrate my fortieth birthday, and there was no way we could have hidden our joy. We celebrated over dinner with a round of cocktails (mine virgin) and I thought about what would need to happen in my life to accommodate this very welcome news. I’d have to sell my apartment as soon as possible, as our family income would be reduced by somewhat more than half. I’d have to push back the publication of this book, as it would come out when I was due to give birth.

Top Comments

Thank you Tara. Reading that felt like reading so much of my own experience and feelings about the way miscarriage is perceived and dealt with (or not). I hope attitudes and awareness will change.

Thank you so much for sharing your story. This year I have suffered both a miscarriage and then a month later, an ectopic pregnancy where I had to make the choice to abort my baby because my life was in danger. I'm an absolute mess and I am finding it hard to function day to day. The hardest part of trying to deal with it alone as friends and family either do not understand or do not want to hear about it. Reading your story makes me feel like I'm not alone in suffering this grief and that I will feel better in time. At the moment I can't see through it but I'm hoping I'll get there. Thankyou...