This article contains discussions of suicide and may be triggering for some readers. For 24-hour mental health crisis support, please call Lifeline on 13 11 14. A trained crisis supporter is ready to take your call.

On the morning of Friday, May 1, 2020, Stina Jensen woke up early.

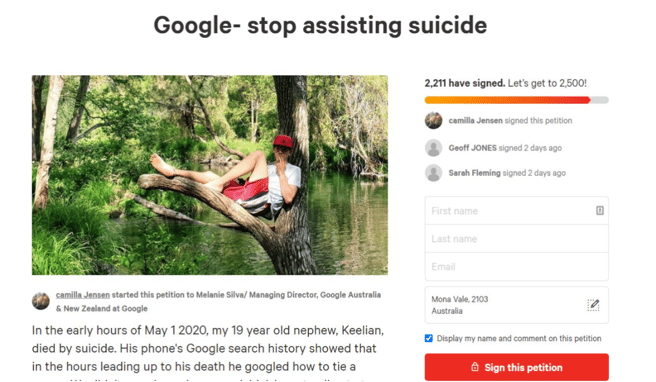

Her 19-year-old son Keelian, who had been living out of home since December last year, was staying over. He’d called her late on the Wednesday night - so late he’d woken her up - asking if she could pick him up from the house he’d been sharing with his girlfriend. They’d had an argument, and for a few days, without telling anyone, he had been staying there alone.

Stina picked him up and once they were back at the family home, Keelian went straight to sleep. The next day was entirely unremarkable. He spent time with his best friend, went for a walk with his 10-year-old sister, and when he went to bed, he told his parents he’d see them in the morning.

Then Stina woke up. It was before 6am.

I didn’t ask her specifically about the chronology of that morning. It seemed too soon and too raw for her to walk me through those moments.

But I do know that not long after 6am, Stina’s sister Camilla received a phone call. She could hear sirens in the background.

At first, perhaps irrationally, she was convinced it would all be okay. Otherwise, she thought, what was the point of the ambulances coming?

But Keelian was already gone. He had taken his own life.