As a young woman I fell pregnant to my boyfriend of two years. The year was 1969. My partner wanted to marry me, but I felt that I was too young and wanted to wait. My parents did not support my decision to keep my child and sent me away from home to work as a housekeeper. I was not allowed to return home until after the birth, and from the time I left home I had no contact with relatives or friends, only my child’s father.

Our local doctor was Catholic and convinced my mother that she was doing ‘the right thing’ in insisting that I adopt out my infant. He suggested that she take me to Crown St., then the largest maternity hospital in NSW. I had to visit first with a social worker before being admitted as a maternity patient. The social worker espoused the benefits of adoption, and commended my mother on her decision to select an adoption plan for my unborn child. I explained that I wanted to keep my baby and that the father and I planned to get married in the future. I was ignored. The social worker listened encouragingly to my mother, who did most of the talking, and reconfirmed my G.P.’s assessment that it was the best plan for both my unborn child and myself. She stated that I would soon put ‘the whole thing behind me and could start my life afresh’. There was never mention of any grief I might experience or possible psychological damage to either myself or my infant as a consequence of our separation. There was no discussion about the available benefits that might assist me to keep my baby.

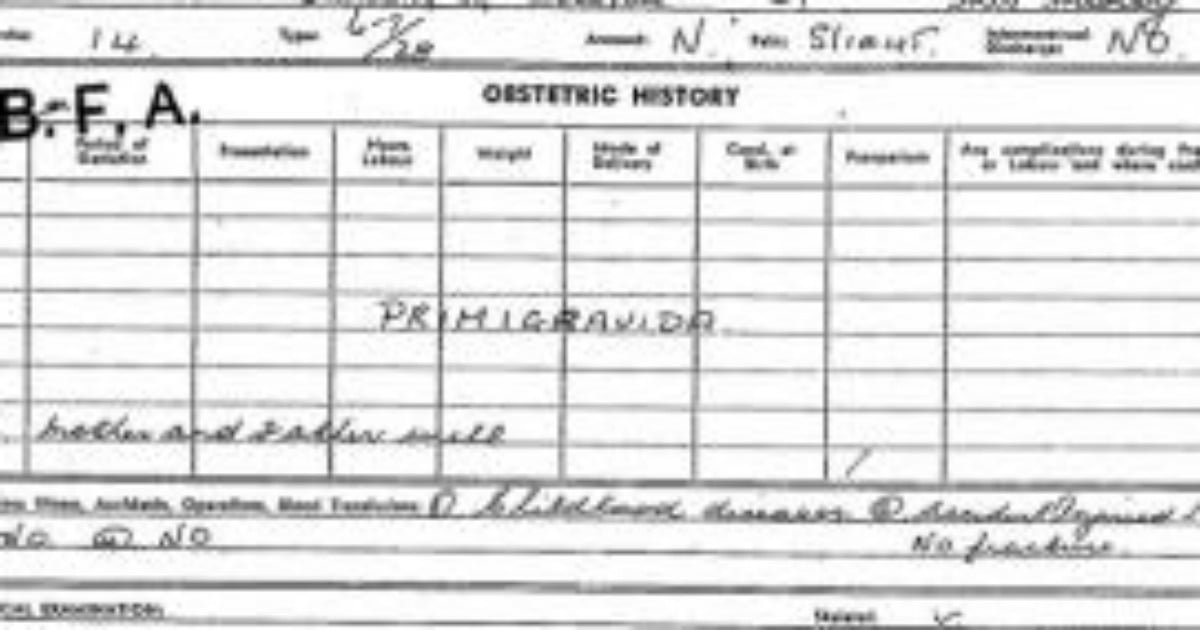

Unbeknownst to me, she marked my file with the code: BFA, ‘Baby For Adoption’, at that first meeting, whilst I was only five months pregnant. This code, as I found out in 1994, when I became involved in adoption rights activism, would guide maternity staff, months later, as to my treatment in the maternity ward. I did say that I wanted to keep my baby, as stated above, and many years later when I gained access to my social work files I saw that the social worker had written: ‘Immature little girl’. Later I would learn that being classified as ‘immature’ was a euphemism for a ‘pregnant girl/woman who wanted to keep her infant’.

Top Comments