Dulcie Bodsworth was the unlikeliest serial killer. She was loved everywhere she went, and the townsfolk of Wilcannia, which she called home in the late 1950s, thought of her as kind and caring.

The officers at the local police station found Dulcie witty and charming, and looked forward to the scones and cakes she generously baked and delivered for their morning tea. That was one side of her. Only her daughter Hazel saw the real Dulcie. And what she saw terrified her.

Dulcie was in fact a cold, calculating killer who, by 1958, had put three men in their graves – one of them the father of her four children, Ted Baron – in one of the most infamous periods of the state’s history. She would have got away with it all had it not been for Hazel.

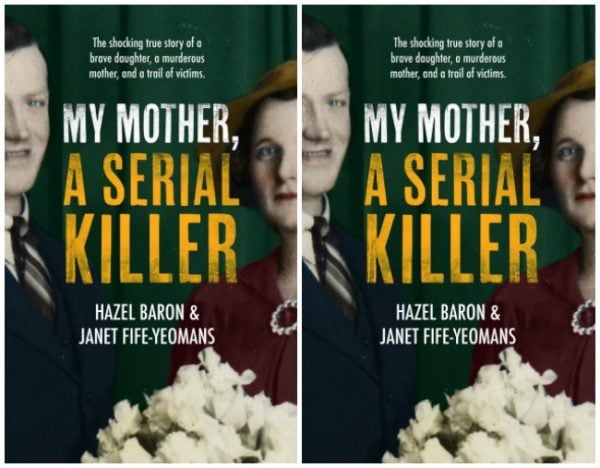

The following piece is an extract from My Mother, A Serial Killer, written by award-winning journalist Janet Fife-Yeomans together with Hazel Baron:

Hazel Baron was nine when she first suspected her mother was a murderer.

Don’t tell your dad about this. Don’t tell your dad about that. Don’t tell him about the sneaky hours in the dark on the big back seat of the family’s American-built Nash car with young Harry, nineteen years her mother’s junior. Harry was only supposed to be ‘helping with the kids’. As a kid herself, Hazel did what she was told and never even considered telling on her mum. Dulcie was also quick with her right hand to dish out a slap or worse. In those days, no one questioned using corporal punishment to keep children in line.