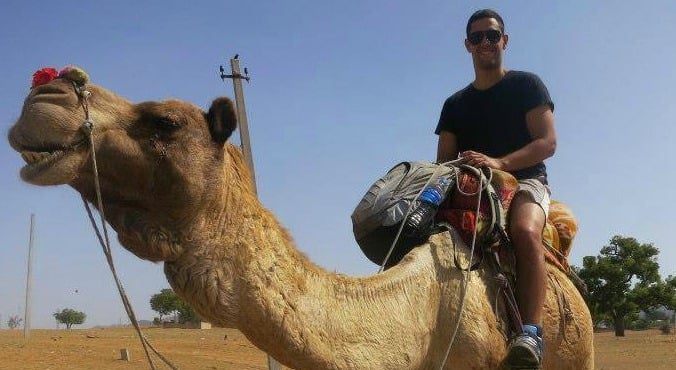

Image: Danny Baker has had such rich experiences since overcoming depression.

Trigger warning: This story deals with themes of depression and suicide.

April, 2010:

The days dragged along. This was the worst I’d ever felt. Period. There was no relief from the ceaseless dread. I could barely function. Paying attention in class was almost impossible. Studying was too overwhelming. I’d fallen absurdly behind. I hadn’t touched my book [that I was writing] in days.

I’d quit my [part-time] job at the law firm, too—needed all my free time to try and catch up on uni. But there was never enough time. I was constantly exhausted. Drained of life. Depression sucked at my soul. My spirit withered. My goal for the day got broken down even further: “just survive the next six hours,” I’d tell myself, “the next four hours. Hold off killing yourself until then.” [At which point I’d tell myself the same thing over again.]

I’d previously thought I’d get better. I’d always thought it true that hope and depression were bitter rivals until one inevitably defeated the other, and I’d always thought that hope would win out in the end. But for the first time in my life, I was void of hope.

I honestly believed that being depressed was just the way I was, and that being depressed was just the way I’d be, for the rest of my life. And because I was so convinced that I’d never get better, there seemed no point in fighting my illness.

Instead of willing myself to “hang in there” because I believed that my suffering was temporary and that everything would be better one day, I comforted myself with the knowledge that human beings are not immortal. That I would die, one day. One special, glorious day. Then I could spend the rest of eternity moulding in a grave, free from pain. You might be wondering why I didn’t just kill myself if I wholeheartedly believed that my future consisted of nothing more than excruciating misery.