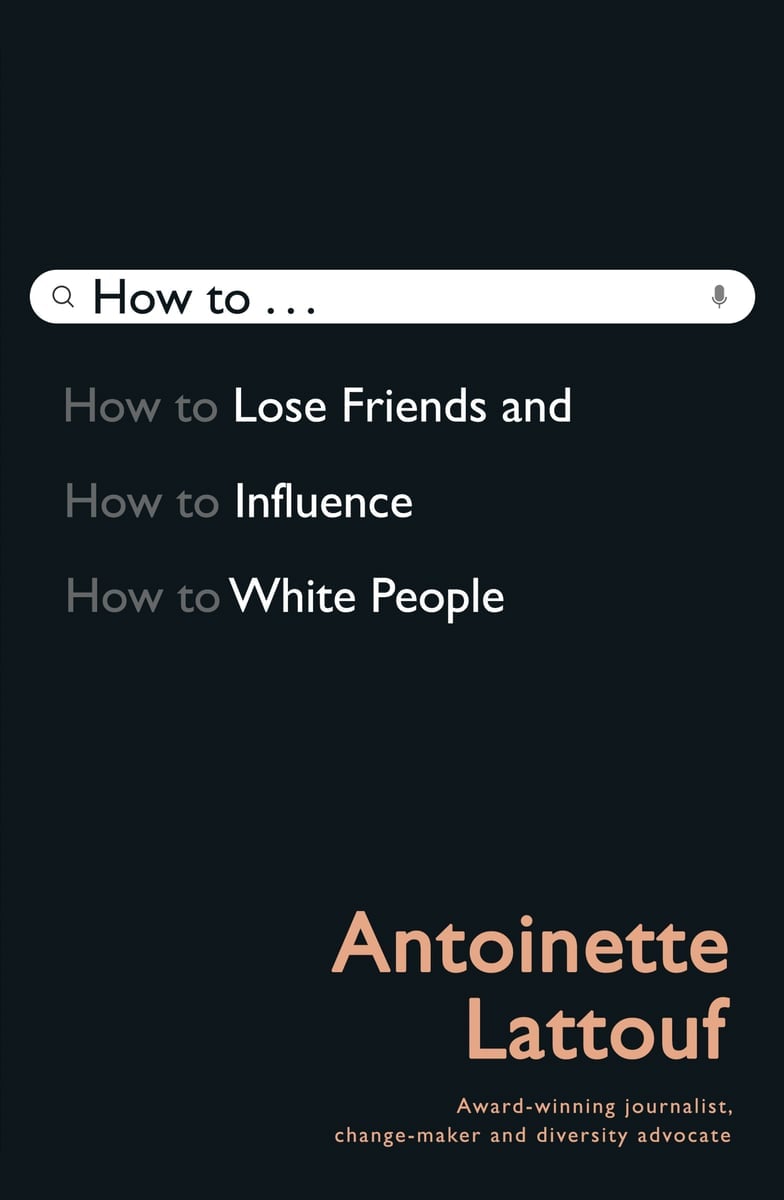

This is an extract from How to Lose Friends and Influence White People by Antoinette Lattouf.

My husband and I attended a very glamorous and lavish wedding.

We walked into the reception hall, decorated with expensive flowers and aromatic scented candles, and I quickly noticed that other than us, there was only one other guest who was a non-white person of colour.

My husband, in particular, stood out – he’s tall, broad and brown-skinned with deep, almost black eyes.

Listen: Antoinette Lattouf talks to Mia Freedman on No Filter about racism, tokenism and inclusion. Post continues below audio.

The bride was a friend of mine from the media, and her husband was a successful entrepreneur. This meant there were plenty of both the moneyed class and television presenter-types in attendance.

The bride looked sensational, and she was so happy. I was thrilled to see her so radiant, and while I had only met her husband one or two times before the big day, I was keen to get to know him more.

We ate, danced, toasted and quickly forgot that we stood out among the rest of those in attendance.

That’s the thing about being a person of colour: you routinely notice when you’re the odd one out and then just move on.

I’m pretty accustomed to it, given that the circles I travel in for work in the media are overwhelmingly white.

Top Comments