To explain any historical event by dismissing one group of people as 'selfish halfwits' would be lazy.

It's also inaccurate and ultimately, wildly unhelpful.

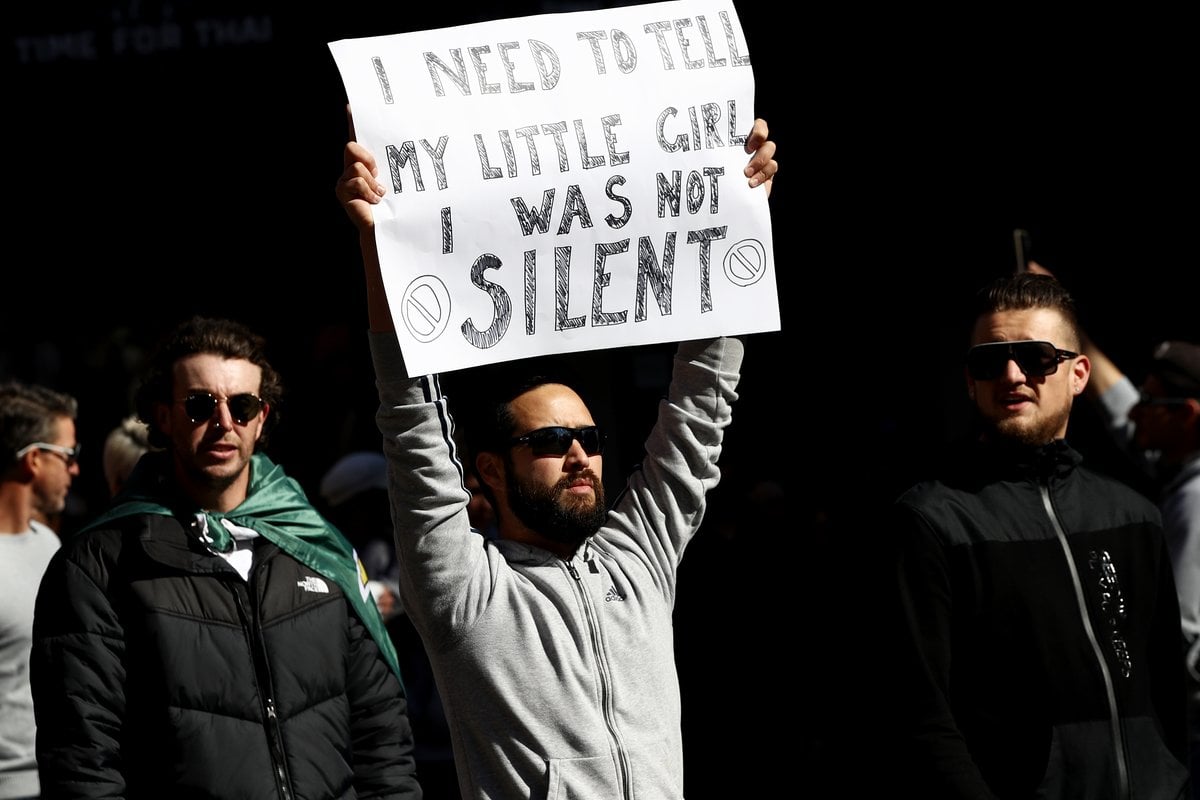

Last weekend, thousands of Australians marched the streets of their capital city. In most of those cities, Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide, this was despite strict stay at home orders implemented to curb the spread of COVID-19.

Compliant Australians watched these so-called 'freedom rallies' unfold from inside their homes. They thought about the sacrifices they've made. The empty funerals. The cancelled events. The kids who can't learn from classrooms and the businesses who are barely staying afloat.

And for what?

For a small group to put their 'freedom' above our safety and promulgate - let's call them what they are - dangerous conspiracy theories, and likely wind back the lockdown clock. While the protestors might not get tested for COVID-19, they have every chance of passing it onto vulnerable family members and to the broader community.

In Sydney, protestors wouldn't have had to walk much further to pass by Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, where a 38-year-old woman lay dying of COVID-19. The virus some of them believe doesn't exist claimed her life a few hours later.

What I mean to say is that our anger makes sense.

But calling them all stupid?

If only it were that simple.

While we were looking at a press photo of a (white) man allegedly assaulting a horse, we were ignoring the faces in the background.

Top Comments