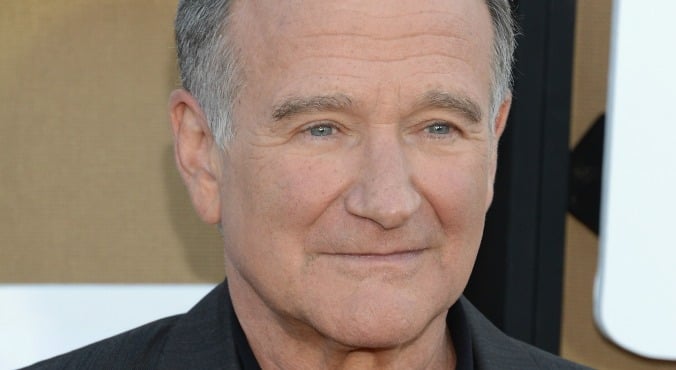

Image: Robin Williams’ suicide last year left the world in shock and mourning (via Getty)

News reports and personal stories of suicide leave many of us wondering what we can do to support the people in our own lives who may be at risk.

It’s easy to feel helpless, but even starting a conversation with someone you’re concerned about can be enough to help them seek the support they need.

The Glow spoke to Dr Michael Player, a psychologist and research officer at the Black Dog Institute, to find out what your action plan should be when you think a loved one might be at risk. Dr Player has recently been heading up research into suicide and poor mental health in men.

How do I know if someone might having suicidal thoughts?

As suicide is often precipitated by a mental illness, a person exhibiting depression, anxiety or substance abuse may be at risk of suicidality. “Initially, you want to be looking at people’s moods, particularly friends and family members who you observe on an ongoing day to day basis,” Dr Player says.

Some signs and symptoms are overt – a person might talk about wanting to die, research methods, or say things like, ‘There’s not much for me to be here for’. Others are sub-symptomatic; for instance, social isolation and withdrawing from contact with loved ones by turning off their phone and not responding to messages. A suicidal person might sleep too much or too little, or talk about feeling like a burden to others.

Giving away belongings, saying goodbye and making contact with people they haven’t seen in a while is a particularly clear signal. “That usually coincides with them suddenly feeling happier or calmer after they’ve been down – that’s often a pattern where someone has made the decision to [end their life], and it relaxes them because that decision has been made,” Dr Player says.