"Can I carry your bags, Madam?"

Dorothy Beencke, 78, was strolling home from her local shops in Sydney's Lane Cove when a man approached her. He was middle-aged, well-dressed, and appeared pleasant. A gentleman, it seemed.

The man lugged Mrs Beencke's groceries the remainder of the short walk down a laneway to her unit.

She offered him a cup of tea in return for his kindness, but he declined and went on his way.

Later that November 2 afternoon in 1989, down that same laneway, that same man bludgeoned 85-year-old Margaret Pahud across the back of the head.

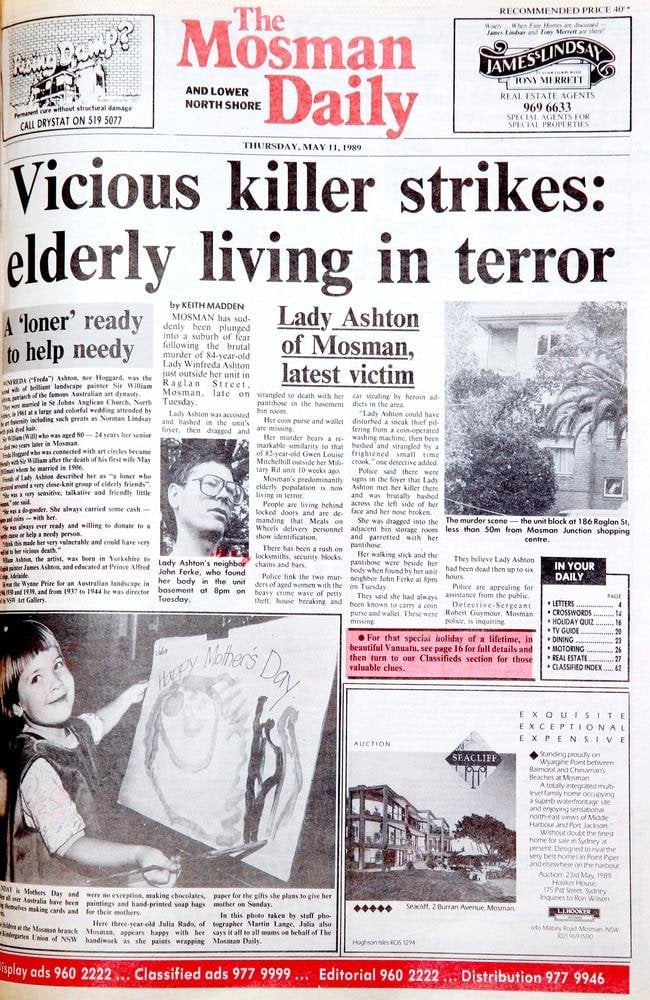

The woman's body was found in a pool of blood. Her clothes had been rearranged, her shoes placed at her feet. Her handbag, stolen. It was the third time in eight months that elderly women on Sydney's north shore had been found this way.

And it wouldn't be the last.

"We were starting to believe we had a serial killer."

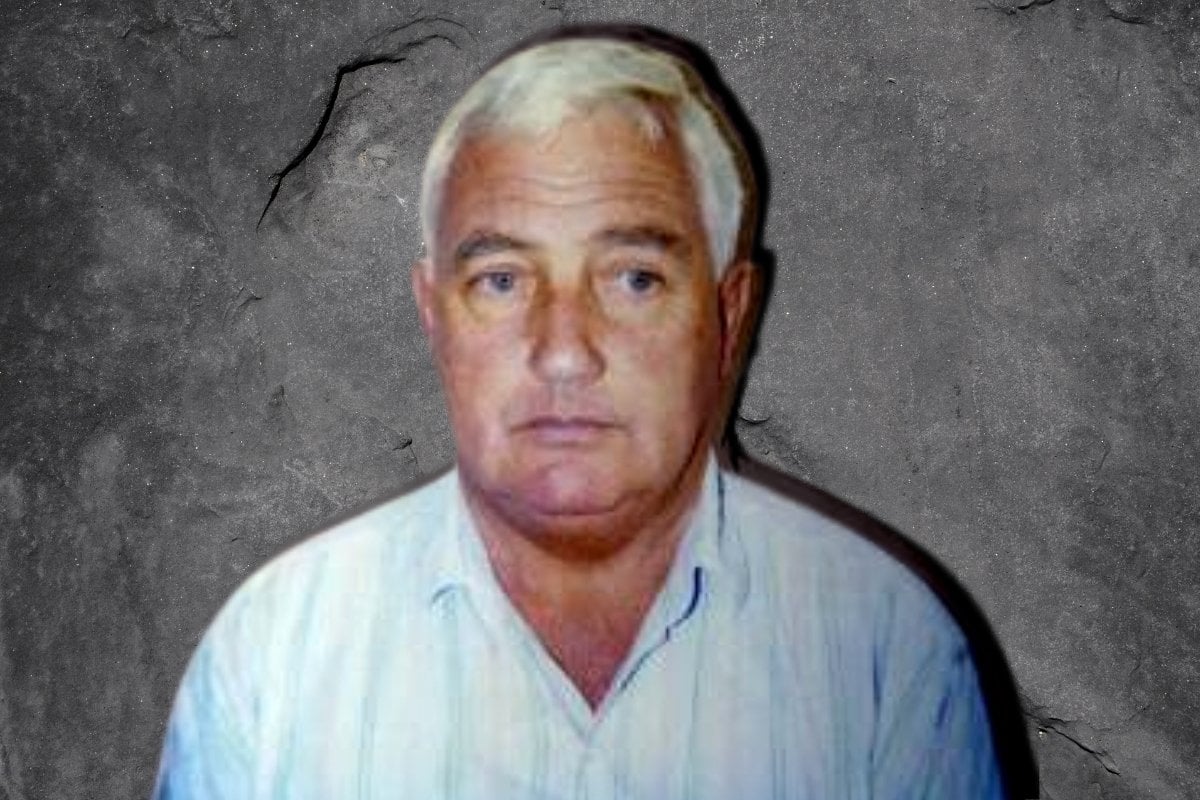

Former Detective Inspector Mike Hagan was among the police officers on the trail of the mystery murderer.

Speaking to Mamamia's True Crime Conversations podcast, he recalled the first time the 'granny killer' — as he'd been dubbed by the press — struck.

The victim was Gwendoline Mitchelhill, an 82-year-old woman who was beaten to death with a hammer at the entry to her Mosman unit block on March 1, 1989. Her handbag was missing, and investigators initially assumed it was a mugging gone wrong.

Top Comments