Warning: The article contains an image and the name of an Indigenous person who has died.

"I can't breathe."

Those three words are echoing across the world this week. They're emblazoned across headlines, social media posts, and cardboard signs, as people join the conversation about the May 25 death of Minneapolis man George Floyd.

As captured in the viral phone footage taken by a bystander, the desperate plea was among the last words the African American man uttered as he lay facedown, dying, with the knee of a white police officer pressing firmly on his neck.

Six years ago, those three words were also among the last uttered by black man Eric Garner after New York City police officers placed him in a fatal chokehold.

With these deaths — and plenty more like them — "I can't breathe" has become a catch-cry of the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States, an evocative symbol of the systematic racism that underpins heavy-handed police tactics across the country.

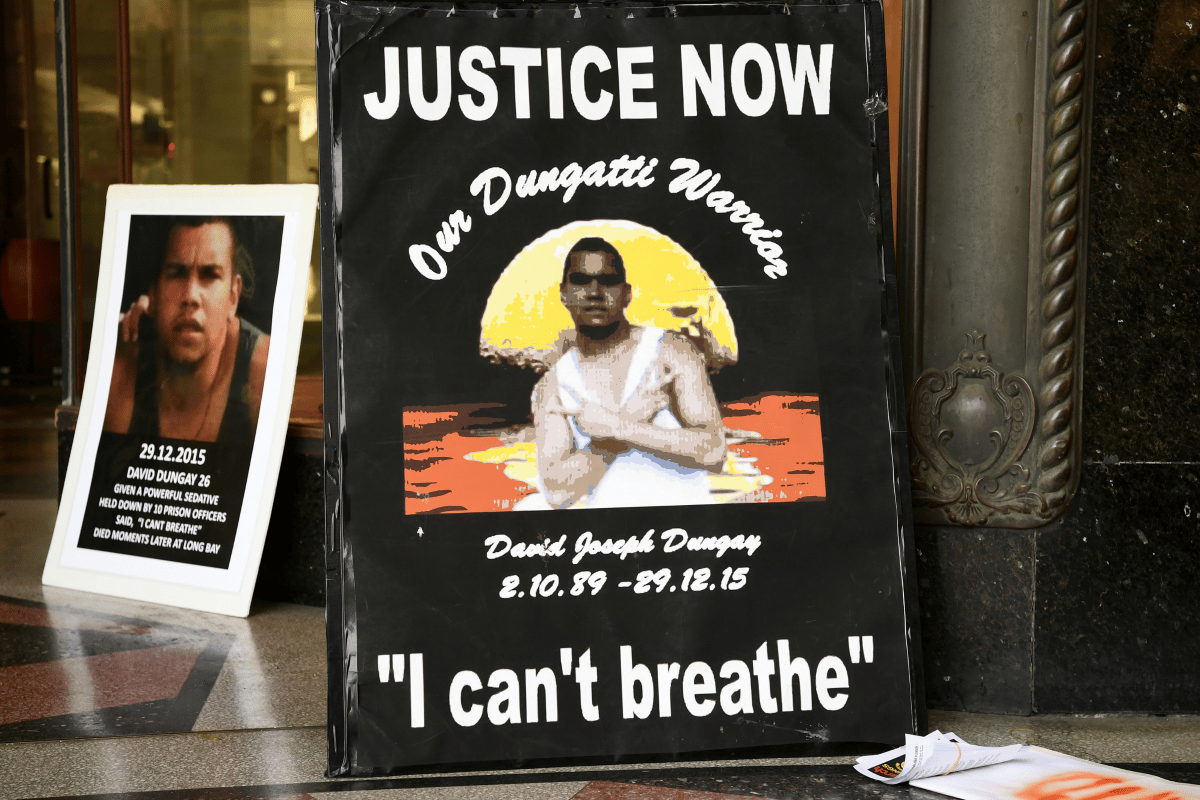

But for the family of Indigenous Australian, David Dungay, the phrase also hits painfully close to home.

David, a 26-year-old Dunghutti man from Kempsey in NSW, died in custody in 2015 after being restrained, sedated and pinned down by five prison guards.