WARNING: This post contains discussions of eating disorders.

For the last three years, Chloe has been slowly dying. Although she is sixteen, she weighs as much as an eight-year-old. We have tried everything the medical system has to offer – psychologists, psychiatrists, family therapists, dieticians, drugs … but nothing has worked.

Anorexia is a difficult thing to get people to understand. Sometimes they will come right out and say what I know they are thinking: ‘Why can’t you just get her to eat?’

The hospital had told us Chloe should be supervised closely for the first few weeks at home, so we devised another system. One of us would stay at home with her while the other went to work. For the first few days, it was Ray’s turn.

I called him many times that first day. ‘How are things going?’

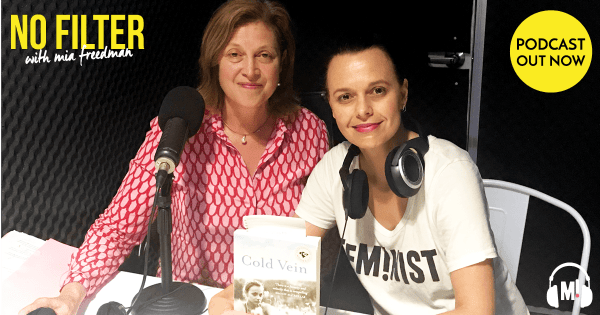

Anne Tonner talks to Mia Freedman about watching her daughter struggle from anorexia. Post continues after audio…

‘Fine. She’s fine.’

‘How did lunch go?’ I persisted. ‘Did you follow the meal plan?’

I could hear the rising tide of exasperation in his voice. ‘If you don’t think I’m capable of looking after her, why don’t you stay home,’ he said.

Chastened, I put down the phone. How had I turned into that sort of mother? Never trusting, always controlling – that had never been me. That night, I arrived home from work to find Ray sitting on the couch watching television with Alice and Jack.