It’s believed that at present, 1 in 70 Australians have coeliac disease, and of these, four out of five remain undiagnosed.

In people who have coeliac disease, defined as a long-term autoimmune disorder, the immune system reacts to gluten causing damage to the small intestine. Gluten is a protein found in wheat, rye, barley and oats, meaning those with coeliac disease need to entirely remove foods containing these elements from their diet.

People with the disease are born with a genetic predisposition, but it’s also thought environment factors play a role in developing coeliac disease throughout a person’s lifetime.

While it might seem like coeliac disease has only recently been discovered (with the ‘fad’ of gluten-free diets and the rapid increase in diagnosis), our knowledge of the condition actually dates back to the 1940s.

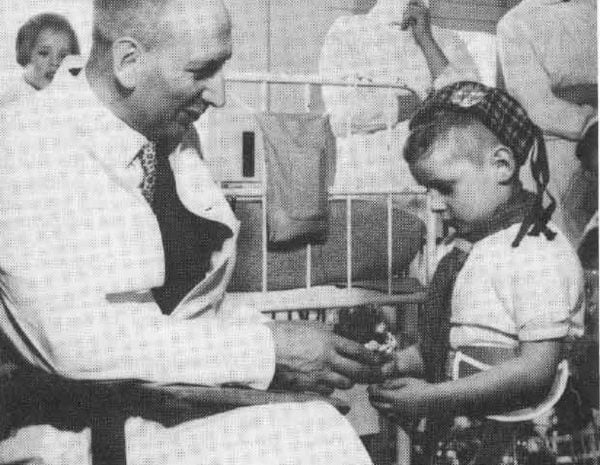

Dutch pediatrician Willem-Karel Dicke was working in a children’s hospital when he published the first report on a wheat-free diet in 1941. In it, he wrote:

“In recent literature it is stated that the diet of Haas (Banana-diet) and Fanconi (fruit and vegetables) gives the best results in the treatment of patients suffering from coeliac disease. At present (World War II) these items are not available. Therefore, I give a simple diet, which is helping these children at this time of rationing. The diet should not contain any bread or rusks. A hot meal twice a day is also well tolerated. The third meal can be sweet or sour porridge (without any wheat flour).”

He gained far more evidence for his hypotheses, however, during the Dutch famine of 1944-1945. The last winter of World War II became known as the ‘Winter of Hunger’, because the delivery of staple foods such as bread were largely disrupted. The population had to turn to less common foods, and Dicke noticed an improvement in the clinical condition of his patients.

Top Comments

Interesting, I never knew this! Kind of a sad silver lining thing.