Spoiler alert: If you haven’t read the book version of The Girl On The Train or haven’t seen the movie yet but want to – do not read ahead.

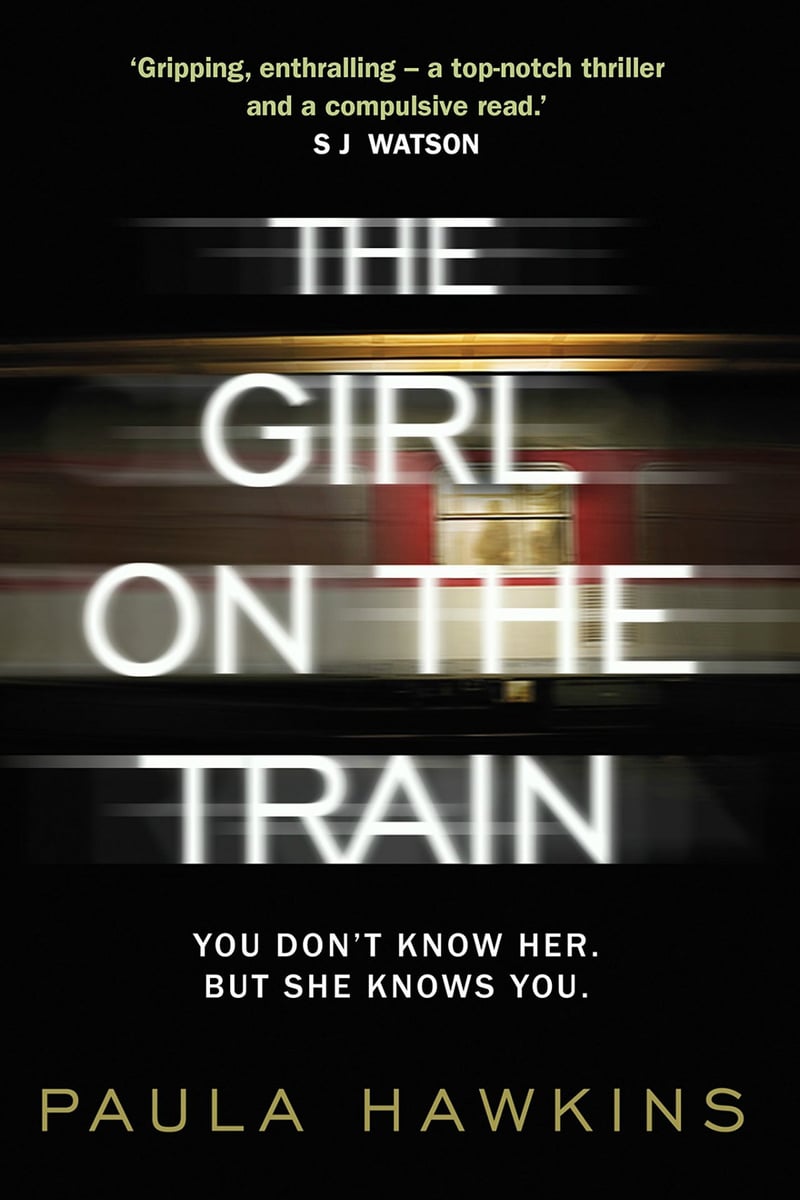

The movie adaptation of Paula Hawkins’ bestselling book, The Girl On The Train, came out in Australia last week.

Like thousands of others around the world (the film topped the North American box office over the weekend, FYI) I flocked, choc top firmly in hand, to watch the thriller played out on the big screen.

Predictably, hordes of reviewers (both of the professional and armchair variety) have come out to dissect just how well/dismally Emily Blunt, who plays main character Rachel, depicted an alcoholic, and just how jarring it was to change the location of the story from London to New York (it was a bit, to be honest).

But there was one part of the film I couldn’t help noticing above all else. It stuck out like a fresh papercut on a finger.

I was fixated by how powerfully the film displays the complexities and confusion that surrounds abusive relationships.