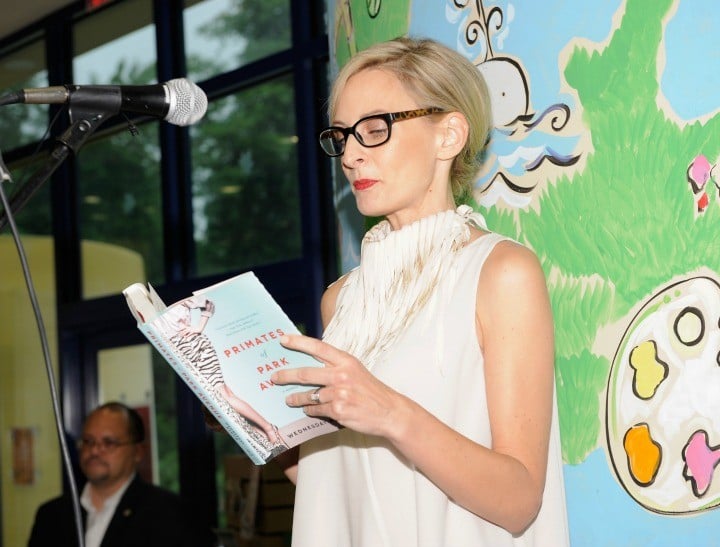

What happens when you go to live among the rich people? Dr Wednesday Martin is a social researcher with a background in anthropology. She moved to Manhattan’s most prestigious ZIP code, the Upper East Side, had a baby and wrote a book. Primates of Park Avenue is an anthropological memoir of Manhattan motherhood, and this is just a tiny part of it.

My OB wisely counseled that childbirth and recovery were “nine months up and nine months down,” like most of my peers, I did not feel I had nine months. I was in a hurry, impatient to be the old, taut me, apprehensive and preoccupied beyond reason that it would never happen.

Mothers all across the country feel a version of this fear; women’s magazines such as Fit Pregnancy and New Mommy Workout and stringent postpregnancy exercise DVDs and online classes attest to our collective terror. But here on the Upper East Side, the anxieties and pressures are greater. Whereas women in Nebraska and Michigan might hop on the treadmill in the basement when they can, and skip Dunkin’ Donuts, and take their time with the last 10 pounds, perhaps resigning themselves to all or a portion of it remaining, my tribe of mommies was another matter. Just as we had to excel at being beautifully pregnant, so, too, we had to be the most gorgeous mothers of infants, babies, toddlers, and young children that it was possible to be.